撰文 | Frank Wilczek

翻译 | 胡风、梁丁当

中文版

想象世间万物可能或应该如何运作,可以帮助我们揭示真实的规律,反之亦然。

想象世间万物可能或应该如何运作,可以帮助我们揭示真实的规律,反之亦然。

18世纪的哲学家戴维·休谟(David Hume)有一个论断:不可能用逻辑的方法从“是什么”推论出“应该是什么”,反之亦然。休谟的论证非常有力,通过区分“事实”与“价值判断”,对科学的范畴与法律、道德的范畴做了清晰的划分,这被哲学家戏称为“休谟的断头台”。

但是逻辑并非一切。为了睿智地思考我们应该做什么,需要先设想未来可能会发生什么,这样我们才能采取相应的行动。这意味着我们需要思考未来,一个充满诸多可能性的未来。

著名的哲学家兼棒球捕手尤吉·贝拉(Yogi Berra)有句名言 :“很难做出预测,尤其是对未来的预测。”尤吉和物理学家可谓是灵犀相通。根据现代物理学,由于相互作用带来的复杂性,再加上量子力学和混沌理论的限制,我们根本无法明确地预测将来。但是,我们可以想象未来的可能性。正是在这个意义上,爱因斯坦说 :“想象力比知识更重要”,因为想象力“涵盖了无限的可能性。”

当我们引入“未来的可能性”这个新的维度,就能够绕开休谟的断头台,构建出一个迷人的三角形。它的三个角分别对应着“是什么”、“可能是什么”和“应该是什么”。有四个箭头将它们连接起来。

第一个箭头从“是什么”指向“可能是什么”。科学的主旨是回答“是什么”。但科学发展到今天,不仅让我们对物质、生命与信息是什么有了深入的理解,也指引了未来可能的方向。从这个角度来说,赫伯特·威尔斯(H.G. Wells)、亚瑟·克拉克(Arthur C. Clarke)、奥克塔维亚·巴特勒(Octavia Butler)、石黑一雄(Kazuo Ishiguro)等人的科幻文学,通过构想未来的世界,对通常来说更加理性化的科研论文作了生动的补充。

第二个箭头从“可能是什么”指向“应该是什么”。这种联系不能通过逻辑或使用通常的科学方法建立。但是,通过想象未来的各种可能性,我们可以对它们进行理智的比较和分析,从中筛选出那些我们所期望的,避免那些我们所不希望出现的。虽然不同的人选择也可能不同,但建立在想象力基础上的相互理解有助于提升讨论的质量。

有两个不同的箭头从“应该是什么”指回“是什么”。第一个很容易理解 :你必须知道想去哪里,才能到达那里。除此之外,还有另一支美丽而神秘的箭头 :想象这个世界应该是怎样的,可以帮助我们猜测它可能的运行方式。不可思议的是,这竟然可以指引我们通往真理。

近代基础物理学和宇宙学的发展都呈现出这个特征。尤金·维格纳(Eugene Wigner)谈论着“数学在自然科学中的不合理有效性”。保罗·狄拉克(Paul Dirac)则写到 :“如果一个人追求优美的数学表达,而他刚好有好的洞察力,那么他就必然会取得进展。”

这些洞见来自他们各自的经验。群论发展于19世纪末,在维格纳把它引入原子的量子力学理论中时,这个理论还很生僻。通过分析电子波函数的对称性,维格纳自然而然地揭示了元素周期表的本质。狄拉克好奇地将狭义相对论和量子理论融合,得到了一个优美的描述电子的数学方程。但这个方程似乎有个致命的缺陷。为了理解这个“缺陷”,狄拉克预言了一个奇妙的新世界 :反物质。

更广泛地讲,通过想象宇宙世界应该有的模样,爱因斯坦发展出了广义相对论,量子物理学家发展出了基本力的现代理论,宇宙学家提出了极其简单的大爆炸模型。简而言之,对未来的无限想象指引着通向真实本身的路。

英文版

Envisioning how things could,and even should work in the universe can help to figure out how they do work-and vice versa.

The 18th-century philosopher David Hume argued that it is impossible to proceed, by purely logical reasoning, from statements about what is to statements about what should be (or vice versa). Hume’s arguments were so forceful and convincing that philosophers still today speak of “Hume’s guillotine,” or the fact/value distinction, which separates the world of science from the world of law and morality.

But logic isn’t everything. To think intelligently about what we ought to do,we must think about what should happen, so that we can act to make it happen. In short, we need to think about futures. That’s futures, with an s. As the famous philosopher and bad-ball hitter Yogi Berra observed, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” Here Yogi anticipated modern trends in quantum mechanics and chaos theory that put fundamental limits on predictability—as does the sheer complexity of the world, with its many interacting parts. But though we can’t predict the future, we can imagine possible futures. It was in this context that Albert Einstein asserted, “Imagination is more important than knowledge,” because imagination “embraces all there ever will be.”

Thinking about futures opens up a charmed triangle that loops around Hume’s guillotine. At the corners are the domains of is, could be and should be. They are linked by four arrows.

The first arrow points from what is to what could be. Science is primarily concerned with what is. But modern science has achieved such fundamental understanding of matter, life, and information that it also provides a solid pointer to what could be. Here, prophetic literature from H.G. Wells and Arthur C. Clarke to Octavia Butler and Kazuo Ishiguro supplements the (usually) more sober scientific literature.

A second arrow points from what could be to what should be. This connection cannot be drawn by logic, or by using normal scientific methods. But upon imagining alternative futures clearly we can compare them intelligently, chooseamong those that are desirable and avoid those that are undesirable. Of course, different people might make different choices, but imaginative understanding elevates the level of discussion.

Two different arrows point from what should be back around to what is. The first is easy to understand: You must know where you want to go in order to get there. But there is another arrow, beautiful and mysterious, pointing in the same direction. It is the remarkable fact, especially characteristic of recent fundamental physics and cosmology, that thinking about how the world should work can lead us to make guesses that turn out to describe how the world does work. Eugene Wigner spoke of “the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences,” and Paul Dirac wrote, “It seems that if one is working from the point of view of getting beauty in one’s equations, and if one has really sound insight, one is on a sure line of progress.”

They spoke from personal experience. Using (formerly) esoteric late 19th-century mathematics, Wigner showed how the periodic table of elements becomes evident within the quantum theory of atoms, once the wave functions of electrons are analyzed into symmetrical patterns. Dirac’s playful fusion of special relativity and quantum theory led him to a beautiful equation for electrons that seemed to have a fatal flaw. But the “flaw,” properly understood, predicted something wonderfully new: antimatter.

More generally, visions of how things should be guided Einstein to general relativity, quantum physicists to our present theories of the other fundamental forces, and cosmologists to their radically simple model of the big bang—in short, to the way things are.

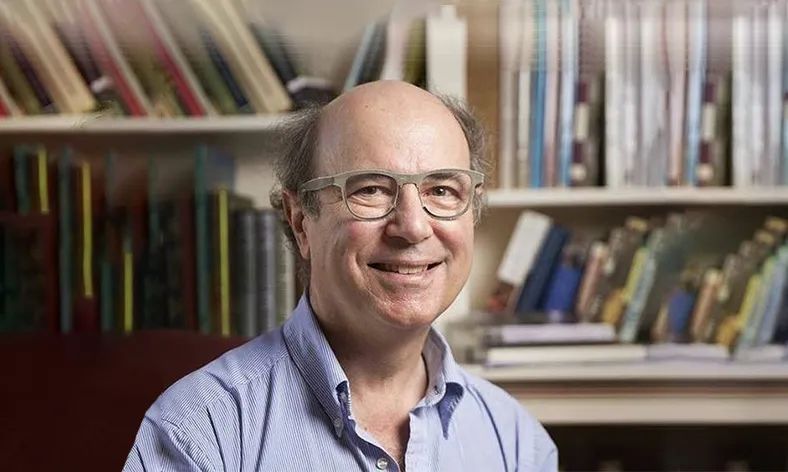

Frank Wilczek

弗兰克·维尔切克是麻省理工学院物理学教授、量子色动力学的奠基人之一。因发现了量子色动力学的渐近自由现象,他在2004年获得了诺贝尔物理学奖。

弗兰克·维尔切克是麻省理工学院物理学教授、量子色动力学的奠基人之一。因发现了量子色动力学的渐近自由现象,他在2004年获得了诺贝尔物理学奖。

本文经授权转载自微信公众号“蔻享学术”,编辑:黄琦。

0

推荐

京公网安备 11010502034662号

京公网安备 11010502034662号